The 50-over format is no more a cosy fit in cricket’s lucrative T20 ecosystem. Come World Cup time, however, the one-day game can again be king. At least for a few days. At least for one more edition…

“When the World Cup rolls around, it’ll be bigger than Ben Hur again.” This was the astute Adam Zampa in October last year, talking to ABC Sport about the relevance – or lack thereof – of ODI cricket. Of course, Zampa went on to express a lot of misgivings about where the 50-over format was currently at, specifically going on to add, “There’s about 10 overs in the middle that needs to be scrapped.”

Be that as it may, we’ve reached that ‘Ben Hur’ moment for ODIs now, at least for the next two months, with a home World Cup complete with the delightful prospect of a couple of India-Pakistan matches. Perhaps these games will bring with them the joyful ebbs and flows of a format which originally awoke a cricketing colossus in 1983.

No doubt the clamour for a long-due World Cup trophy in India’s cabinet will also reach a crescendo if the hosts start off with a couple of good wins. For the moment, administrators can give their t axed brain cells a breather over what to do with the sport’s ‘nothing-special’ middle child. After all, our cricket-loving population is more than willing to gloss over fundamental questions come World Cup festival time.

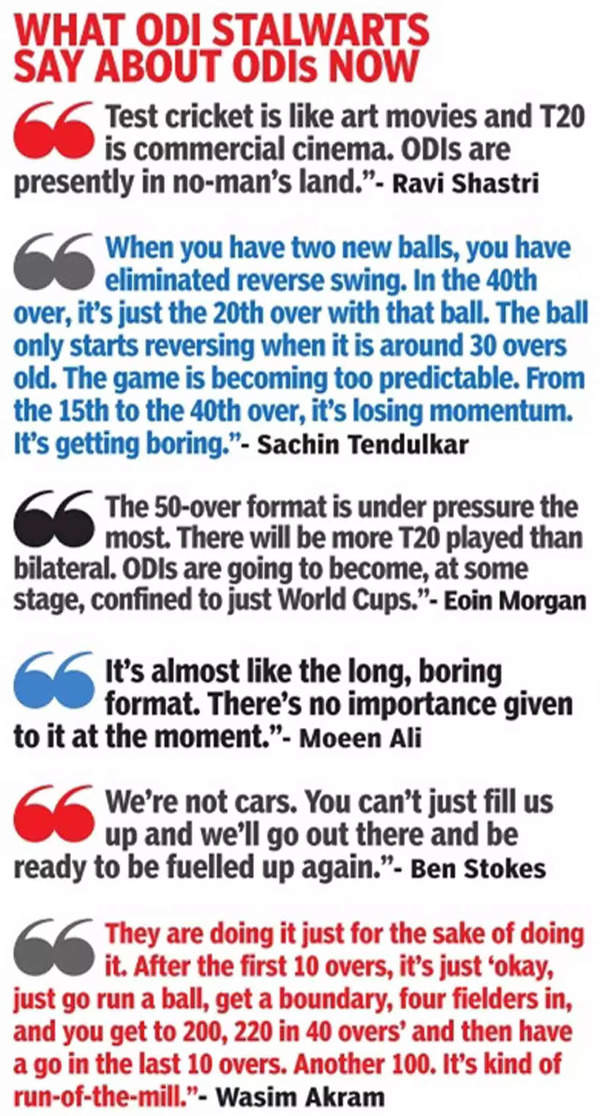

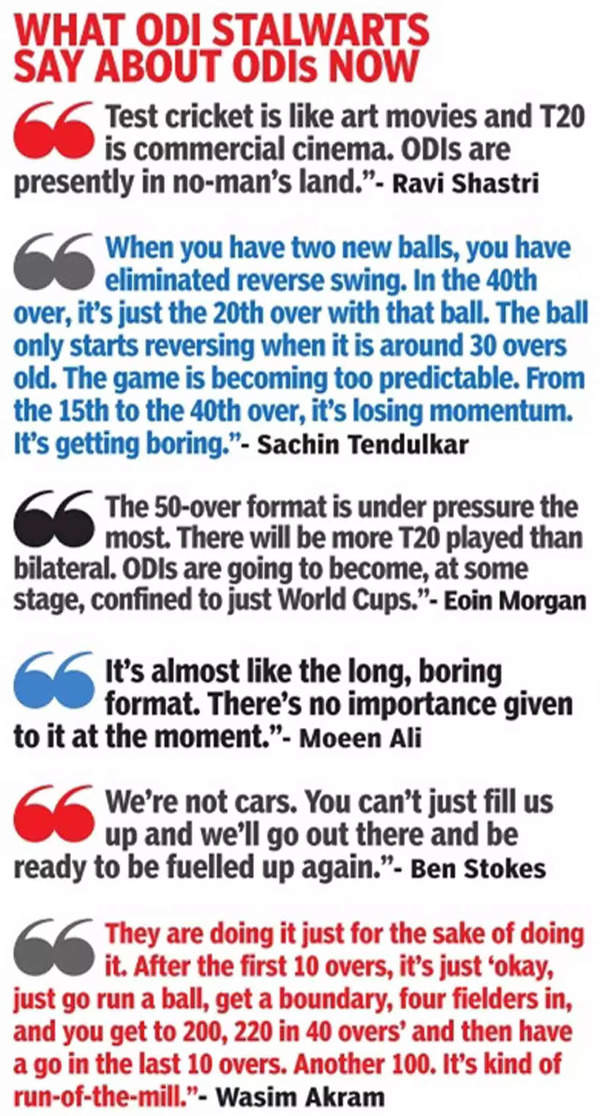

It is, however, only momentary respite. For cricket’s power brokers, ODIs are now a chronic headache outside the World Cup environment. Over time, the notion that the middle overs were getting boring meant the 50-over format was altered beyond recognition with countless tweaks, setting limitations for captains and bowlers and taking reverse swing and old-ball trickery out of the equation with new balls at either end.

ODIs now largely resemble an extended mix of a T20 ditty, demanding higher and higher batting strikes and desperate bowling variations to cope with coma-inducing hitting sprees. Field restrictions have meant the captain’s hands are tied.

The average batting strike rate in each World Cup went up from 54.52 in 1979 to 78.39 in 2011 – the last time India won at home, also the time the T20 spirit started seeping in – to 88.97 in 2015 and 88.15 in England in 2019.

The tournament grew from an overall 2 centuries in 1979 to 38 hundreds in 48 matches in 2015. Between the 2015 and 2019 World Cups, before the Covid lull set in, there were 53 scores of 350-plus, including 5 scores above 400. From the 2019 WC to now, even with months lost to the pandemic, there have been 25 scores of 350-plus, with 4 of the m above 400. The format’s natural moments of quiet and consolidation are now derided by impatient fans more used to gorging on a T20 diet.

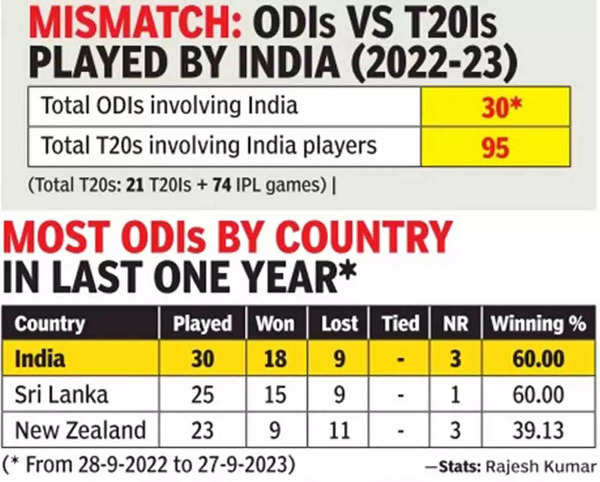

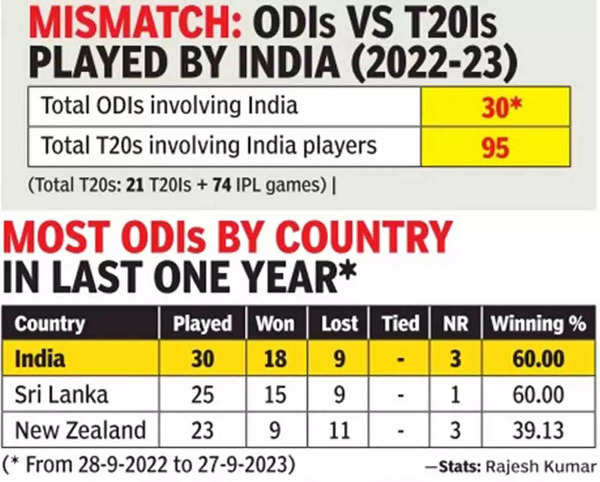

The ODI finds itself being gradually elbowed out by a lengthier IPL window, mushrooming private T20 leagues and a bursting international calendar. Many top cricketers are willing to give the format the short shrift by forgoing central contracts and devoting themselves to T20 subsistence. The now-abandoned ODI WC Super League had its flaws and wasn’t well received either. There is a notion that the best days of the ODI may have co me and gone. Administrators have tried responding with defiance. Over the past year, India’s cricketers have played a total of 95 T20s – IPL and internationals included – and 30 ODIs.

These are the most ODIs for any team in this period, while Australia have played the least (14). For India, the corresponding figures stood at 68 T20s and 27 ODIs in the year leading up to the 2011 WC. Worryingly, close games have been few and far between. Of the 326 ODIs played in the two years leading up to this WC, only 17 have seen victory margins of less than 10 runs, and only 18 games have been won by less than 3 wickets. Cricket’s dystopian future was evident after the completion of the T20 World Cup in Australia last year, when champions England had to stay back to play a meaningless 3-ODI bilateral series.

Clearly, something had to give. In July, the Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC) recommended limiting bilateral ODIs after the 2027 World Cup to “improve quality and create space in the calendar”. The MCC said “the suggestion is that a scarcity of ODI cricket will increase the quality”. No doubt the “space” created will be filled by more franchise T20s, with the IPL’s deep-pocket owners now out shopping for new teams in overseas leagues.

Cricket has a new, lucrative ecosystem outside ODIs now. The format may not long remain relevant outside the World Cup cycle. If Tests are already a novelty, ODIs may become a rarity. They are simply eating into T20 time.

The nature of games in this edition may well decide the future of bilateral ODIs, if not the 50-over World Cup itself. A generous public response will reprise the good old times and for a while, wipe away the tears from cricket’s forlorn middle child.

“When the World Cup rolls around, it’ll be bigger than Ben Hur again.” This was the astute Adam Zampa in October last year, talking to ABC Sport about the relevance – or lack thereof – of ODI cricket. Of course, Zampa went on to express a lot of misgivings about where the 50-over format was currently at, specifically going on to add, “There’s about 10 overs in the middle that needs to be scrapped.”

Be that as it may, we’ve reached that ‘Ben Hur’ moment for ODIs now, at least for the next two months, with a home World Cup complete with the delightful prospect of a couple of India-Pakistan matches. Perhaps these games will bring with them the joyful ebbs and flows of a format which originally awoke a cricketing colossus in 1983.

No doubt the clamour for a long-due World Cup trophy in India’s cabinet will also reach a crescendo if the hosts start off with a couple of good wins. For the moment, administrators can give their t axed brain cells a breather over what to do with the sport’s ‘nothing-special’ middle child. After all, our cricket-loving population is more than willing to gloss over fundamental questions come World Cup festival time.

It is, however, only momentary respite. For cricket’s power brokers, ODIs are now a chronic headache outside the World Cup environment. Over time, the notion that the middle overs were getting boring meant the 50-over format was altered beyond recognition with countless tweaks, setting limitations for captains and bowlers and taking reverse swing and old-ball trickery out of the equation with new balls at either end.

ODIs now largely resemble an extended mix of a T20 ditty, demanding higher and higher batting strikes and desperate bowling variations to cope with coma-inducing hitting sprees. Field restrictions have meant the captain’s hands are tied.

The average batting strike rate in each World Cup went up from 54.52 in 1979 to 78.39 in 2011 – the last time India won at home, also the time the T20 spirit started seeping in – to 88.97 in 2015 and 88.15 in England in 2019.

The tournament grew from an overall 2 centuries in 1979 to 38 hundreds in 48 matches in 2015. Between the 2015 and 2019 World Cups, before the Covid lull set in, there were 53 scores of 350-plus, including 5 scores above 400. From the 2019 WC to now, even with months lost to the pandemic, there have been 25 scores of 350-plus, with 4 of the m above 400. The format’s natural moments of quiet and consolidation are now derided by impatient fans more used to gorging on a T20 diet.

Why KL Rahul should continue as first-choice wicketkeeper-batter

The ODI finds itself being gradually elbowed out by a lengthier IPL window, mushrooming private T20 leagues and a bursting international calendar. Many top cricketers are willing to give the format the short shrift by forgoing central contracts and devoting themselves to T20 subsistence. The now-abandoned ODI WC Super League had its flaws and wasn’t well received either. There is a notion that the best days of the ODI may have co me and gone. Administrators have tried responding with defiance. Over the past year, India’s cricketers have played a total of 95 T20s – IPL and internationals included – and 30 ODIs.

These are the most ODIs for any team in this period, while Australia have played the least (14). For India, the corresponding figures stood at 68 T20s and 27 ODIs in the year leading up to the 2011 WC. Worryingly, close games have been few and far between. Of the 326 ODIs played in the two years leading up to this WC, only 17 have seen victory margins of less than 10 runs, and only 18 games have been won by less than 3 wickets. Cricket’s dystopian future was evident after the completion of the T20 World Cup in Australia last year, when champions England had to stay back to play a meaningless 3-ODI bilateral series.

Clearly, something had to give. In July, the Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC) recommended limiting bilateral ODIs after the 2027 World Cup to “improve quality and create space in the calendar”. The MCC said “the suggestion is that a scarcity of ODI cricket will increase the quality”. No doubt the “space” created will be filled by more franchise T20s, with the IPL’s deep-pocket owners now out shopping for new teams in overseas leagues.

Cricket has a new, lucrative ecosystem outside ODIs now. The format may not long remain relevant outside the World Cup cycle. If Tests are already a novelty, ODIs may become a rarity. They are simply eating into T20 time.

The nature of games in this edition may well decide the future of bilateral ODIs, if not the 50-over World Cup itself. A generous public response will reprise the good old times and for a while, wipe away the tears from cricket’s forlorn middle child.

Source link