Unless you are an avid reader of all things concerning world trade, Tuesday’s spat between India and Thailand at the ongoing World Trade Organisation (WTO) conference may have come as a surprise. The Thai ambassador to WTO accused India of exporting rice at unfairly low prices funded by govt subsidies. The subsidies, the allegation goes, that are meant to supply low-price rice to India’s poor, are actually subsidising the country’s rice exports.

Indian delegation protested the claim, lodged a complaint, taking strong exception to the statement.

The incident is only the latest spark to fly off the contentious issue of agriculture trade that has divided countries for over two decades. India and Indonesia, along with other developing nations, are pushing for reforms in rules governing agriculture trade. The current rules don’t allow them enough freedom to support their farmers and the poor, who need free or subsidised food.

The background

Back in 1994, the WTO set up an agreement to lower import taxes and subsidies that affect agriculture. Here’s how subsidies are categorised:

Green Box:

These are subsidies that don’t really affect trade much. They include direct payments, general services and environmental programmes. There’s no limit on these.

Blue Box:

These subsidies are supposed to be cut down over time. They’re mainly used by rich countries – and China – and are tied to how much land is farmed or crop yield.

Development Box:

It allows developing countries to provide input subsidies to low income or resource-poor farmers and investment subsidies for agriculture.

Amber Box:

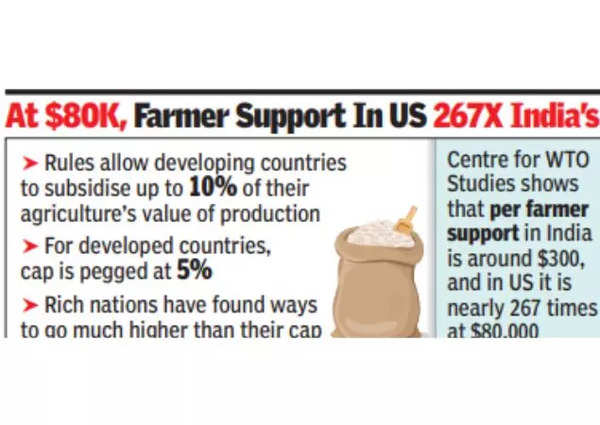

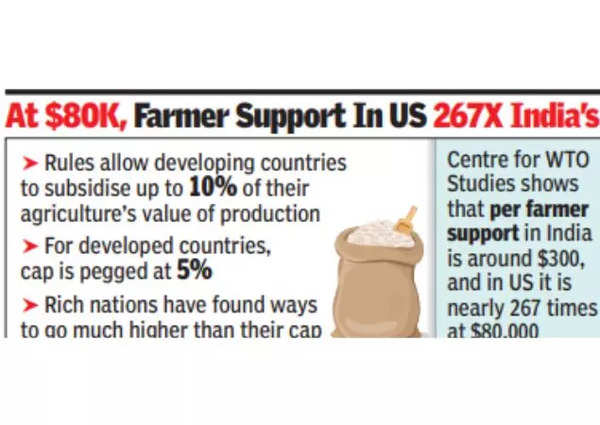

Most other subsidies fall here. They can make farming and trade unfair because they might encourage overproduction or lower prices too much. The rules allow developing countries to subsidise up to 10% of their agriculture’s value of production. For developed countries, the cap is 5%. But rich countries have found ways to go much higher than their cap. For instance, a paper by the Centre for WTO Studies estimated that EU was providing 150% of its sugar’s value of production as subsidy, and the US 189% to coffee.

Why Are Developing Countries Upset?

Why Are Developing Countries Upset?

The rules favour wealthier nations, giving them more ways to support their farmers and dominate the global market. This makes it harder for poorer countries to compete. For example, India has exceeded the 10% subsidy limit for rice, and others might too. The prices, set in the 1980s as a reference for what counts as a subsidy, are outdated, not accounting for inflation or current market prices.

Farms are small in India, which makes government support vital. There is also the need to keep food in stock for the poor during crises like the Covid pandemic or global conflicts.

Calculations by Centre for WTO Studies show that per farmer support in India is around $300, whereas in US it is around $80,000. So, an American farmer, with average land holding of 180 hectare, gets 267 times what a tiller gets in India, where average land holding is just above one hectare.

What’s Being Done?

This issue was first raised in 2002 but became a hot topic in 2013. To move forward with trade discussions, developed countries agreed to a ‘peace clause’ that prevents disputes over subsidy limits. Since then, India and others have been pushing to find a permanent solution.

Current Status

For the past decade, groups representing developing and poorer countries have been asking for a permanent fix but claim rich nations aren’t keeping their promises.

What Do Developed Countries Say?

Rich countries think public stockholding programmes distort trade. They’ve accused developing countries like India of exporting subsidised grains. This is where Thai ambassador’s Wednesday allegation comes in. They’re calling for a major reform to lower tariffs and subsidies. However, there’s disagreement among them, with the EU resisting tariff cuts, unlike the US and other countries seeking broader changes.

Indian delegation protested the claim, lodged a complaint, taking strong exception to the statement.

The incident is only the latest spark to fly off the contentious issue of agriculture trade that has divided countries for over two decades. India and Indonesia, along with other developing nations, are pushing for reforms in rules governing agriculture trade. The current rules don’t allow them enough freedom to support their farmers and the poor, who need free or subsidised food.

The background

Back in 1994, the WTO set up an agreement to lower import taxes and subsidies that affect agriculture. Here’s how subsidies are categorised:

Green Box:

These are subsidies that don’t really affect trade much. They include direct payments, general services and environmental programmes. There’s no limit on these.

Blue Box:

These subsidies are supposed to be cut down over time. They’re mainly used by rich countries – and China – and are tied to how much land is farmed or crop yield.

Development Box:

It allows developing countries to provide input subsidies to low income or resource-poor farmers and investment subsidies for agriculture.

Amber Box:

Most other subsidies fall here. They can make farming and trade unfair because they might encourage overproduction or lower prices too much. The rules allow developing countries to subsidise up to 10% of their agriculture’s value of production. For developed countries, the cap is 5%. But rich countries have found ways to go much higher than their cap. For instance, a paper by the Centre for WTO Studies estimated that EU was providing 150% of its sugar’s value of production as subsidy, and the US 189% to coffee.

The rules favour wealthier nations, giving them more ways to support their farmers and dominate the global market. This makes it harder for poorer countries to compete. For example, India has exceeded the 10% subsidy limit for rice, and others might too. The prices, set in the 1980s as a reference for what counts as a subsidy, are outdated, not accounting for inflation or current market prices.

Farms are small in India, which makes government support vital. There is also the need to keep food in stock for the poor during crises like the Covid pandemic or global conflicts.

Calculations by Centre for WTO Studies show that per farmer support in India is around $300, whereas in US it is around $80,000. So, an American farmer, with average land holding of 180 hectare, gets 267 times what a tiller gets in India, where average land holding is just above one hectare.

What’s Being Done?

This issue was first raised in 2002 but became a hot topic in 2013. To move forward with trade discussions, developed countries agreed to a ‘peace clause’ that prevents disputes over subsidy limits. Since then, India and others have been pushing to find a permanent solution.

Current Status

For the past decade, groups representing developing and poorer countries have been asking for a permanent fix but claim rich nations aren’t keeping their promises.

What Do Developed Countries Say?

Rich countries think public stockholding programmes distort trade. They’ve accused developing countries like India of exporting subsidised grains. This is where Thai ambassador’s Wednesday allegation comes in. They’re calling for a major reform to lower tariffs and subsidies. However, there’s disagreement among them, with the EU resisting tariff cuts, unlike the US and other countries seeking broader changes.

Source link